By John D’Amore, President and Chief Strategy Officer, Diameter Health

By John D’Amore, President and Chief Strategy Officer, Diameter Health

Twitter: @DiameterHealth

Initiatives to measure the quality of healthcare delivered in the United States are not new. The Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures are the primary mechanism used to evaluate and compare the quality of care provided to health plan members. HEDIS was developed over two decades with oversight by the National Committee for Quality Assurance as a reliable, robust program for quality measurement (NQCA Website, 2017). Health plan members gather longitudinal claims data on covered patients and from this perspective, a holistic view of patient care may be achieved.

The “Meaningful Use” portion of the “Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act” enacted in 2009 required that health providers purchase quality measurement technology as part of their certified EHRs so that the EHR would consolidate and replace programs consisting of a mix of paper-based and electronic process. The thesis behind packaging quality measurement into certified EHR technology was that all information pertinent to the patient and care quality would be recorded inside or transmitted to the care systems used by a single provider. This contrasts significantly with the historic methodology used in the HEDIS program, where data from all sites of care are aggregated to calculate quality measures with no expectation that a single provider would have all the relevant data. While there continues to be consolidation of providers and health systems on a shared EHR particularly in acute care settings, the reality is that most patients, particularly patients with complicated health issues that are the focus of many of the quality measures, see many physicians across multiple practices using different EHRs. In discussions with Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), we estimate that the average ACO will need to aggregate data from 15-30 EHRs in their network to accurately measure care quality for all patients.

Consider how this EHR-centric system fails both the patients and the providers being measured. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) and Merit Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) programs have increasing impact on physician reimbursement. Currently, 50% of 2018 MIPS dollars are allocated based on the quality of care with the impact increasing over time. While physicians can self-select the measures they report on, most providers use the EHR functionality for reporting.

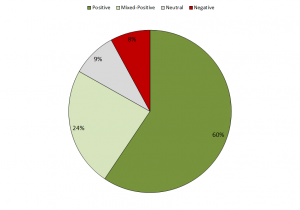

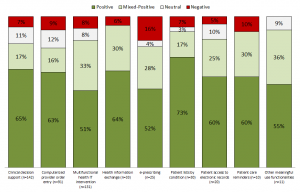

Let’s consider the example of a diabetic patient. The patient sees their primary care physician who records problems of diabetes and hypertension but does not record an HbA1c result. The patient sees their cardiologist who records problems of heart failure and hypertension and the HbA1c level. And finally, the patient visits their endocrinologist who records diagnoses of diabetes and heart failure and results of an HbA1c diagnostic. Reporting just from their respective EHRs, only the endocrinologist is compliant on the measure of HbA1c control (see figure 1). The cardiologist is missing documentation of diabetes as a problem so the patient is not eligible for this measure. The PCP is missing the HbA1c result so is shown as non-compliant for this patient for this measure.

In reality, a patient has only one state of compliance for each measure. The compliance shown in figure 1 for each physician is not representative of the quality of the care the patient received. This does a disservice to physicians as reimbursement is impacted. In the complex world of patient management, not every physician needs to provide every aspect of care for a patient. We don’t want physicians performing duplicative diagnostics, nor do we want patients subjected to redundant care that drives up costs.

Consider what happens when we look at the compliance from the holistic patient perspective (figure 2). The patient is monitored for the HbA1c levels and presumably appropriate treatment. When the information is consolidated across all physicians and visits, we see a more accurate representation of care and all physicians are compliant for this measure. This methodology is in line with how the HEDIS measures were initially envisioned – the consolidation of all of the information across all providers.

For ambulatory quality measures, using electronic data provides benefits over the traditional HEDIS view, where the lag time between clinical care and claims data availability (which may take months) makes measuring progress in real-time difficult. The ability to measure physician performance serially in near real-time provides the opportunity to take appropriate action based on relevant data. This benefits physicians who can then receive the financial benefit of quality measure compliance, but more importantly, patients benefit by receiving appropriate care.

While the potential benefits of a longitudinal patient view are obvious, and the drawbacks of EHR centric quality reporting even more so, substantive data interoperability challenges remain to integrate heterogenous EHR data. Four million clinicians documenting care in over one hundred certified EHRs continue to produce clinical data that requires normalization, deduplication, and enrichment to adequately support clinical quality reporting. Now that most clinicians are using EHRs with the capability to share data digitally, natural language processing and clinical inference can be increasingly applied to refine raw clinical data into useful data substrate for clinical quality reporting and other analytic purposes. Such technology will be necessary as care payment migrates from a fee-for-service to value-based models. Recent research has demonstrated that this is possible (Applied Clinical Informatics, 2018) and both patient and payers should demand it. Longitudinal approaches to quality measurement have been the basis of HEDIS for decades and no less rigor should be accepted for clinical systems that function to improve care.