By Ashish Jha

By Ashish Jha

Twitter: @ashishkjha

Get a group of health policy experts together and you’ll find one area of near universal agreement: we need more transparency in healthcare. The notion behind transparency is straightforward; greater availability of data on provider performance helps consumers make better choices and motivates providers to improve. And there is some evidence to suggest it works. In New York State, after cardiac surgery reporting went into effect, some of the worst performing surgeons stopped practicing or moved out of state and overall outcomes improved. But when it comes to hospital care, the impact of transparency has been less clear-cut.

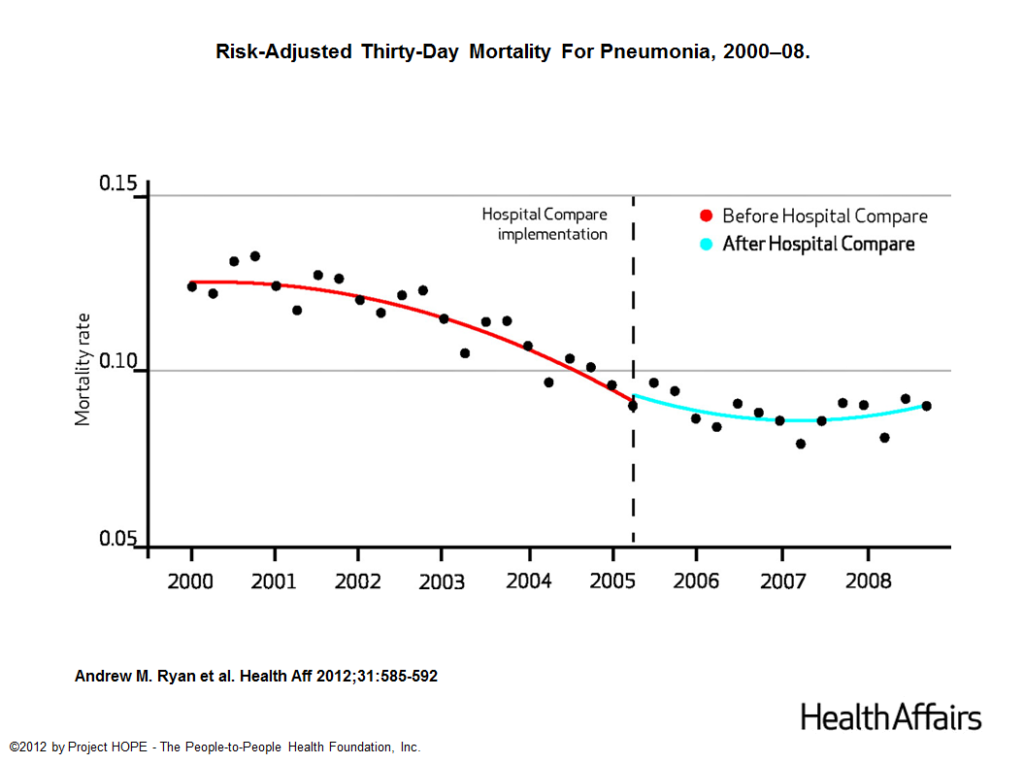

In 2005, Hospital Compare, the national website run by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), started publicly reporting hospital performance on process measures – many of which were evidence based (e.g. using aspirin for acute MI patients). By 2008, evidence showed that public reporting had dramatically increased adherence to those process measures, but its impact on patient outcomes was unknown. A few years ago, Andrew Ryan published an excellent paper in Health Affairs examining just that, and found that more than 3 years after Hospital Compare went into effect, there had been no meaningful impact on patient outcomes. Here’s one figure from that paper:

The paper was widely covered in the press — many saw it as a failure of public reporting. Others wondered if it was a failure of Hospital Compare, where the data were difficult to analyze. Some critics shot back that Ryan had only examined the time period when public reporting of process measures was in effect and it would take public reporting of outcomes (i.e. mortality) to actually move the needle on lowering mortality rates. And, in 2009, CMS started doing just that – publicly reporting mortality rates for nearly every hospital in the country. Would it work? Would it actually lead to better outcomes? We didn’t know – and decided to find out.

Does publicly reporting hospital mortality rates improve outcomes?

In a paper released on May 30 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, we – led by the brilliant and prolific Karen Joynt – examined what happened to patient outcomes since 2009, when public reporting of hospital mortality rates began. Surely, making this information public would spur hospitals to improve. The logic is sound, but the data tell a different story. We found that public reporting of mortality rates has had no impact on patient outcomes. We looked at every subgroup. We even examined those that were labeled as bad performers to see if they would improve more quickly. They didn’t. In fact, if you were going to be faithful to the data, you would conclude that public reporting slowed down the rate of improvement in patient outcomes.

So why is public reporting of hospital performance doing so little to improve care? I think there are three reasons, all of which we can fix if we choose to. First, Hospital Compare has become cumbersome and now includes dozens (possibly hundreds) of metrics. As a result, consumers brave enough to navigate the website likely struggle with the massive amounts of available data.

A second, related issue is that the explosion of all that data has made it difficult to distinguish between what is important and what is not. For example – chances that you will die during your hospitalization for heart failure? Important. Chances that you will receive an evaluation of your ejection fraction during the hospitalization? Less so (partly because everyone does it – the national average is 99%). With the signal buried among the noise, it is hardly surprising that that no one seems to be paying attention — and the result is little actual effect on patient outcomes.

The third issue is how the mortality measures are calculated. The CMS models are built using Bayesian “shrinkage” estimators that try to take uncertainty based on low patient volume into account. This approach has value, but it’s designed to be extremely conservative, tilting strongly towards protecting hospitals’ reputation. For instance, the website only identifies 23 out of the 4,384 hospitals that cared for heart attack patients as being worse than the national rate – about 0.5%. In fact, many small hospitals have some of the worst outcomes for heart attack care – yet the methodology is designed to ensure that most of them look about average. If a public report card gives 99.5% of hospitals a passing grade, we should not be surprised that it has little effect in motivating improvement.

Fixing public reporting

There are concrete things that CMS can do to make public reporting better. One is to simplify the reports. CMS is actually taking important steps towards this goal and is about to release a new version that will rate all U.S. hospitals one to five stars based on their performance across 60 or so measures. While the simplicity of the star ratings is good, the current approach combines useful measures with less useful ones and uses weighting schemes that are not clinically intuitive. Instead of imposing a single set of values, CMS could build a tool that lets consumers create their own star ratings based on their personal values, so they can decide which metrics matter to them.

Another step is to change the approach to calculating the shrunk estimates of hospital performance. The current approach gives too little weight to both a hospital’s historical performance and the broader volume-outcome relationship. There are technical, methodological issues that can be addressed in ways that identify more hospitals as likely outliers and create more of an impetus to improve. The decision to only identify a tiny fraction of hospitals as outliers is a choice – and not inherent to public reporting.

Finally, CMS needs to use both more clinical data and more timely data. The current mortality data available on CMS represents care that was delivered between July 2011 and June 2014 – so the average patient in that sample had a heart attack nearly 2 ½ years ago. It is easy for hospitals to dismiss the data as old and for patients to wonder if the data are still useful. Given that nearly all U.S. hospitals have now transitioned towards using electronic health records, it should not be difficult to obtain and build risk-adjusted mortality models that are superior and remains current.

None of this will be easy, but it is all doable. We learned from the New York State experience as well as that of the early years of Hospital Compare that public reporting can have a big impact when there is sizeable variation in what is being reported and organizations are motivated to improve. But with nearly everyone getting a passing grade on website that is difficult to navigate and doesn’t differentiate between measures that matter and those that don’t, improvement just isn’t happening. We are being transparent so we can say we are being transparent. So, the bottom line is this – if transparency is worth doing, why not do it right? Who knows, it might even make care better and create greater trust in the healthcare system. And wouldn’t that be worth the extra effort?

About the Author: Dr. Ashish K. Jha is a practicing Internist physician and a health policy researcher at the Harvard School of Public Health. This article was originally published on his blog, An Ounce of Evidence.